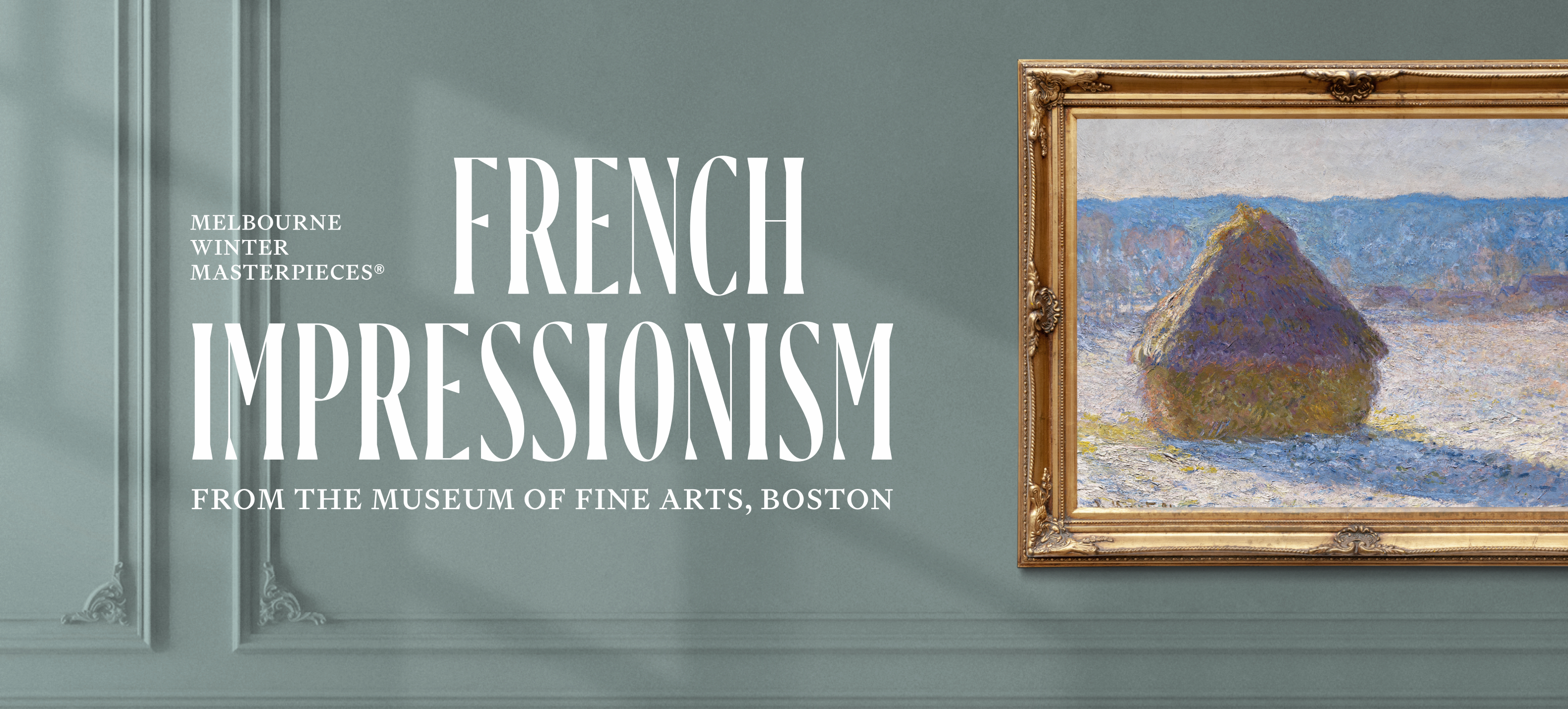

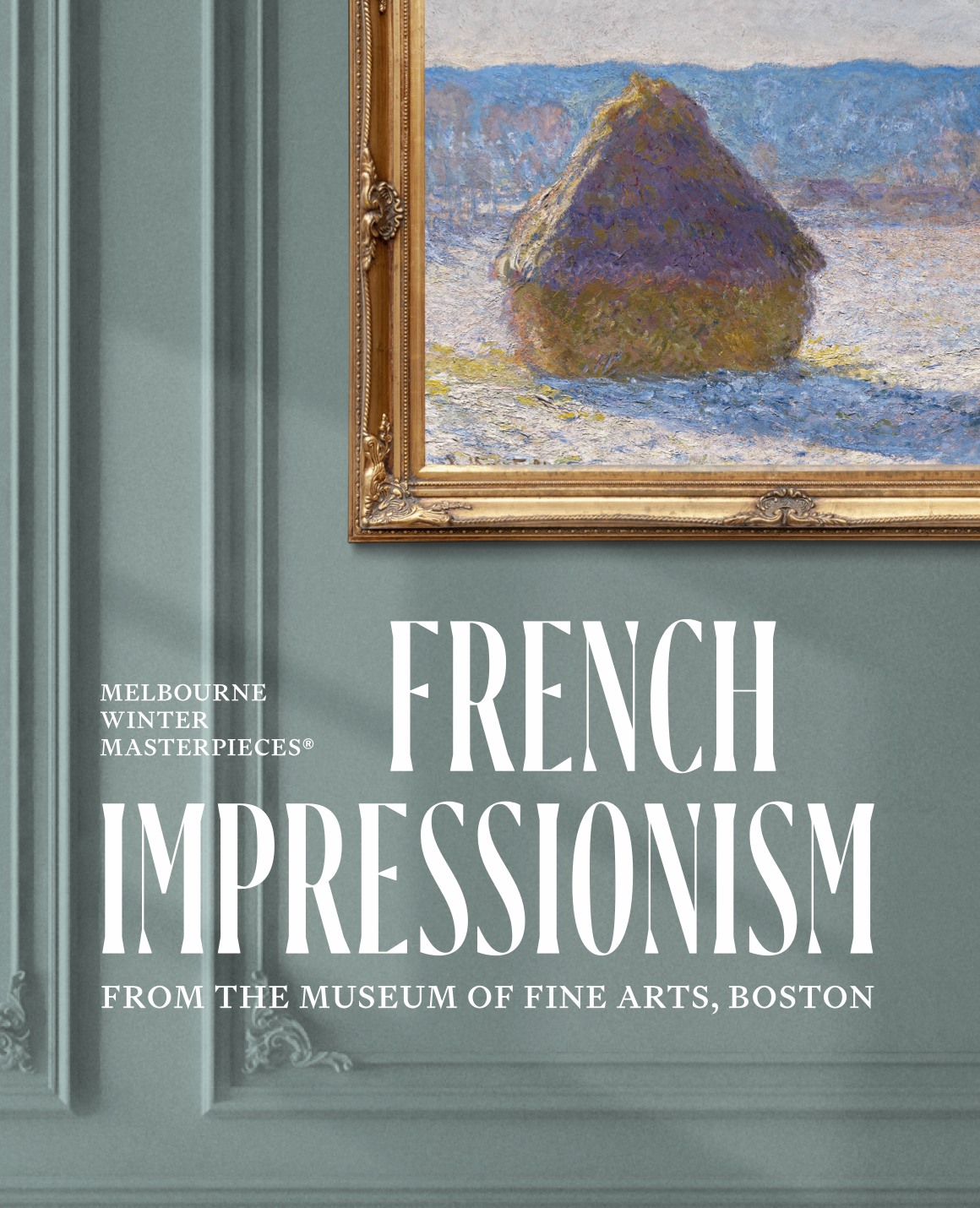

They are Impressionists in the sense that they render not the landscape, but the sensation produced by the landscape.

– Jules-Antoine Castagnary

In 1874, a group of artists in Paris formed a society for the purpose of exhibiting their work independently of the Salon, the official exhibition program the French government established in 1748. This new group staged eight public exhibitions between 1874 and 1886, revealing an approach to painting that privileged ‘impressions’ – often painted en plein air (outdoors, directly in front of the subject) – over what the selecting judges for the Salon considered ‘finished’ works, which were highly academic in style and painted entirely in the studio. In critical responses to these independent exhibitions, this daring, varied and ambitious new painting became known as Impressionism.

The Impressionists were united by a common belief that they should respond to and represent the world around them. This was not a world populated by traditional art historical subjects, such as gods and goddesses, biblical figures or heroic military leaders. Instead, their attention was on the world in which they lived and worked, with a primary focus on nature.

Social connections among the artists also played an important role in the development of Impressionism. These artists knew each other and each other’s work, and held strong opinions on the aims, limits and directions of their own art and the art world of their time. They wrote to and about one another, they sometimes painted side by side, and they exhibited together. Throughout the exhibition are extracts from letters, journal entries and other primary sources, which connect the artists’ voices to the fresh and inspiring vision for which Impressionism is so celebrated.

The role of artistic camaraderie is evoked in this pair of quintessentially Impressionist paintings by Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Monet and Renoir met as art students in Paris, and undertook numerous painting excursions together in the 1860s. Both artists loved to capture radiant outdoor light and vegetation, painting scenes suggestive of leisure and ease. Although their foci differed, both Renoir and Monet were committed to painting the world around them as they saw it, directly in front of the subject and en plein air (outdoors).

Audio Description Tour

Audio Description Tour