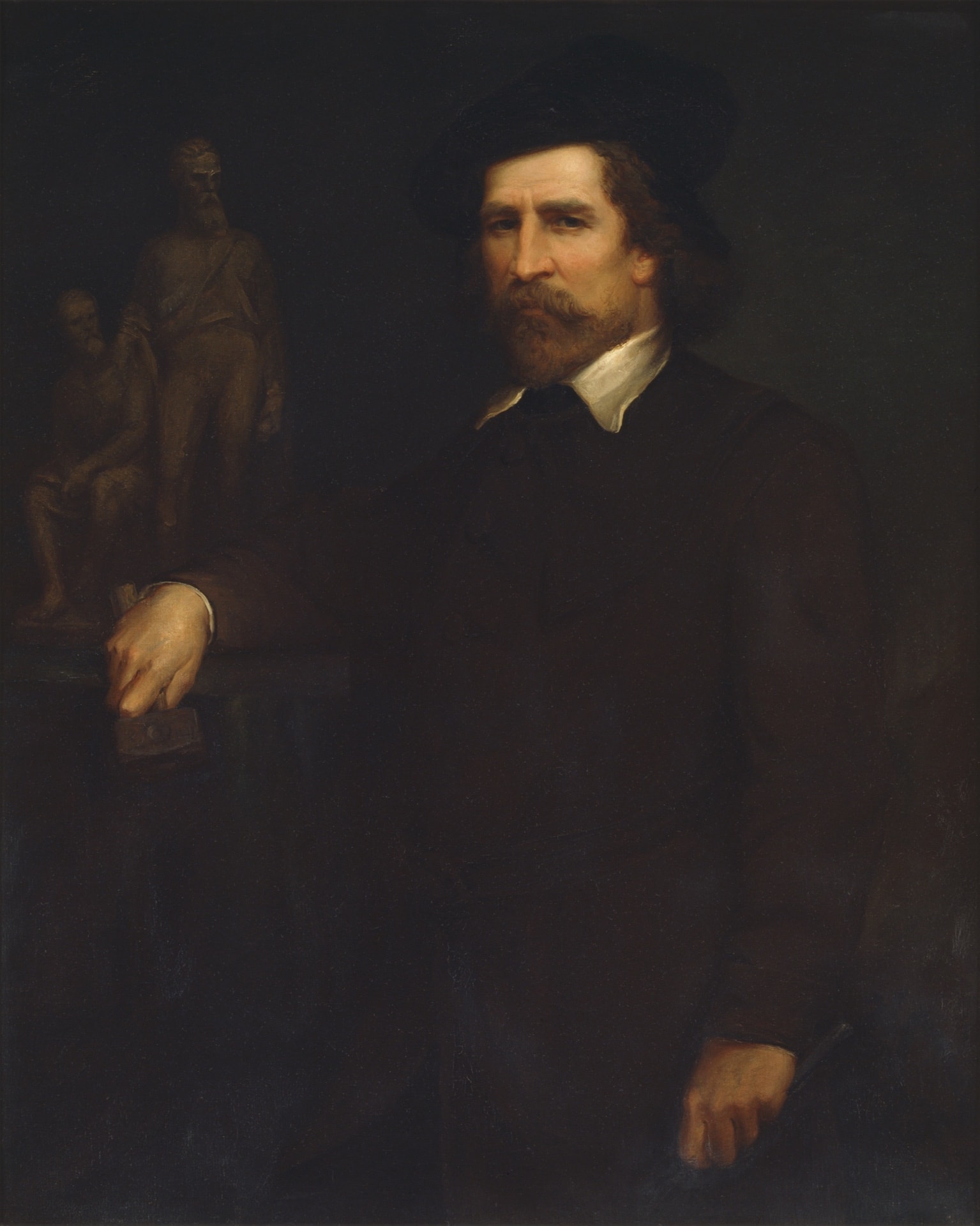

For many years Margaret Thomas’s Charles Summers, c. 1879 (fig. 1), hung prominently in the National Gallery of Victoria, one of a group of portraits of distinguished individuals honoured for their part in the early history of the Colony of Victoria. Acquired in 1881, it is also a foundational work in the history of the Gallery’s collection as one of the first works by an Australian female artist to be acquired.1 The question of what the first work by an Australian female artist to be acquired was revolves around the definition of who is considered an Australian artist. This is a problematic concept if narrowly defined by place of birth or citizenship rather than place within Australian art history. The same criteria must be applied to Thomas as to artists like Tom Roberts, who is always considered an Australian artist. Like Thomas, Roberts was born in England and came to Australia as a child, and both received their first artistic education and began their careers in Australia. Ellis Rowan’s 1887 watercolour, Flower painting, purchased in 1890, was incorrectly identified in Jennifer Phipps, Creators & Inventors: Australian Women’s Art in the National Gallery of Victoria, The Gallery, Melbourne, 1993, as the first work by an Australian female artist to enter the collection. Phipps would have been correct to call Rowan the first ‘Australian-born professional’ female artist, however, whether the amateurs ‘Miss Black’ or ‘Miss Blyth’ (whose works were acquired in 1869 and 1872 respectively) were also Australian-born, is not known. This paper will examine the circumstances of the creation of this work and its acquisition by the Gallery, as well as the remarkable life and career of Margaret Thomas.2 This paper was delivered at the conference ‘Human Kind: Transforming Identity in British and Australian Portraits, 1700–1914’, 8–11 Sep. 2016, University of Melbourne. While today she is an almost forgotten figure with few of her works in public collections, Thomas is nevertheless one of the most interesting Australian artists of the second half of the nineteenth century. During her lifetime she was well-known in both Australia and England as a painter and sculptor, a published poet and author of eight books on travel and art.

The early life and work of Margaret Thomas was closely linked with that of Charles Summers, her first teacher and mentor. In the late 1850s and into the 1860s Summers was Melbourne’s foremost sculptor, one of its most prominent artists and an instigator of its early art societies. He was born in Somerset, England, in 1825 and was the son of a stonemason. As a young man he apprenticed to sculptor Henry Weekes and subsequently to Musgrave Watson. In 1849 he gained admission to the Royal Academy schools where he became the first student to win both the gold medal for best historical group and the silver medal for the best model from life. In 1854, Summers emigrated to Australia where he unsuccessfully sought to make his fortune on Victoria’s goldfields.3 The year of Summers’s arrival in Australia has previously been given in various publications as either 1852 or 1853. R. T. Ridley confirms the date as 16 Jan. 1854, when Charles Summers, his wife Augustina, two of his siblings (Albert and Elizabeth) and his father George arrived in Melbourne on The Hope. See footnote 10 in R. T. Ridley, ‘The mysterious James Gilbert: the forgotten sculptor 1854–85’ in La Trobe Journal, no. 54, March 1995,<http://latrobejournal.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-54/latrobe-54-031.html>, accessed 6 June 2018. By 1855 he had returned to Melbourne and took up a studio in Collins Street. His career took off in 1856 when he received the commission for the carving and modelling of the Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly chambers of Victoria’s Parliament House. Summers quickly established himself at the centre of Melbourne’s small art community, and his studio as ‘the rendez-vous of whoever in those early colonial days practiced or loved art in any way’.4 Margaret Thomas, A Hero of the Workshop and a Somerset Worthy, Charles Summers, Sculptor: The Story of His Struggles and Triumph, Hamilton, Adams & Co, London, 1879, p. 27. In 1856 he was a founding member of the first art society in Melbourne, the Victorian Society of Fine Arts, and in 1861 became the first president of the Victorian Academy of Fine Arts, its annual exhibitions held in his studio until 1864. Significantly, Summers was also closely associated with the establishment of the NGV. In 1863 he was the only artist among the eleven members of the Commission on the Fine Arts (which also included Redmond Barry and James Smith) to recommend the establishment of a dedicated ‘picture gallery’, the acquisition of a permanent collection of original works of art, annual exhibitions of the work of local artists, and the setting up of a school of design (drawing). Summers also received extensive patronage from the Gallery. By 1880 there were twenty-one works by Summers in the collection, including nine marble portrait busts of prominent citizens, and he can be regarded as a kind of ‘official sculptor’ to the fledgling colony.5 These are listed in Ken Scarlett, Australian Sculptors, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980, p. 624. All were deaccessioned in the 1940s under the directorship of Daryl Lindsay. In 1996 the NGV purchased two marble busts by Summers.

Undoubtedly, Summers’s greatest success was his Burke and Wills monument commissioned by the Victorian Parliament and originally sited on the intersection of Collins and Russell streets. It was unveiled on 21 April 1865, the fourth anniversary of Burke, Wills and King’s return to Cooper’s Creek. The ceremony was witnessed by the expedition’s sole survivor John King.6 The monument was, however, not completed until September 1866, when the last of four bas-relief panels were attached to the pedestal. The sculpture was the largest bronze casting ever undertaken in Australia, and as Melbourne’s most prominent work of art at the time, it was a source of great civic pride.

Two years later, in May 1867, Summers left Melbourne permanently. He established a successful studio workshop in Rome, which was the centre of sculpture production in the nineteenth century. There Summers continued to work on commissions for Australian patrons – the most significant being four life-size seated statues of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and the Prince and Princess of Wales commissioned in 1876 by W. J. Clarke for presentation to the NGV.7 These sculptures were deaccessioned in 1941 by incoming NGV Director Daryl Lindsay and given as permanent gifts to public entities. They were installed outdoors, which led to their degradation through exposure. See Gerard Vaughan, ‘The cult of the Queen Empress: royal portraiture in colonial Victoria’, Art Journal, NGV, vol. 50, <https://ngv-assets.exhibitionist.digital/essay/the-cult-of-the-queen-empress-royal-portraiture-in-colonial-victoria/>, accessed 6 June 2018. These royal portraits were the apogee of his career and he worked on them for almost two years. Summers died unexpectedly soon after their completion in October 1878 while en route to Australia to supervise their installation.

Thomas began studying with Summers in 1855 when she was only twelve years old. She was born Margaret Cook on 23 December 1842 in Croydon, Surrey, into a middle-class mercantile family, subsequently taking as her professional name a combination of her mother’s and father’s first names. In 1852 the family emigrated to Victoria and settled in Melbourne, although little is known of Thomas’s family or early life, and it is not known what propelled her to study with Summers. What is clear is that she was a precocious talent. In December 1857, at the age of fifteen, she exhibited a portrait medallion at the inaugural exhibition of the Victorian Society of Fine Arts.

Over the next decade, Thomas regularly exhibited paintings and sculptures in Melbourne and beyond, including two sculptures at the 1861 Intercolonial Exhibition in Melbourne (which were also sent to the 1862 London International Exhibition), and five paintings, one sculpture and a medallion at the 1866 Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition. She was regarded as Summers’s most gifted student; in 1863 critic James Smith wrote that ‘her essays in sculpture betoken the diligent exercise of no ordinary plastic skill and contain the promise of future excellence’.8 ‘The exhibition of fine arts’, The Argus, 5 Jan. 1863, p. 5. She was also one of the very first, if not the first, female art students in Victoria. In 1881, she is referred to in a letter from the Trustees of the NGV as being ‘the first pupil in the Schools of Design and Painting in Victoria’.9 Letter from the National Gallery of Victoria Trustees to Margaret Thomas, 28 July 1881, Library Trustees’ Outward letter-book 1875–1890, Australian Manuscripts Collection, SLV, pp. 391–2. I am grateful to Gerard Hayes, Librarian in the Pictures Collection at the SLV, for bringing this letter to my attention. In later accounts of her life she is consistently referred to as being one of the first three students granted permission to copy from plaster casts in the Gallery.10 I have not been able to confirm where the often-repeated claim that she was ‘one of the first three students granted permission to draw from the plaster casts in the National Gallery’ first originated. Presumably it came from Thomas herself. Thomas’s Bust of Homer, c. 1865, now in the Art Gallery of Ballarat’s collection, is a copy of a cast in the collection of the Melbourne Public Library (now State Library Victoria). These had been collected between 1859–62 by Redmond Barry, President of the Trustees, and placed on display within the Library building on Swanston Street.11 While from 1863 there had been calls for the establishment of an art school associated with the Gallery, the first School of Design was only established in association with the Gallery in June 1867. Although it is possible that Thomas was briefly enrolled just before leaving for England, it is more likely that her access to the casts was facilitated by Summers, in the period before the establishment of the School of Design. See Kathleen M. Fennessy, ‘For “love of art”: the Museum of Art and Picture Gallery at the Melbourne Public Library 1860–70’, The La Trobe Journal, no. 75, Autumn 2005, p. 13, <http://latrobejournal.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-75/t1-g-t2.html>, accessed 6 June 2018.

Around July 1867, Thomas left Australia, bound for London to continue her studies, a precursor to the pattern of expatriatism of Australian art students to study in London and Paris that was a feature of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.12 The exact date of her departure is not known; however the Geelong Advertiser of 14 Sep. 1868 mentions her departure 15 months earlier, making it sometime around July 1867. See ‘Current topics’, Geelong Advertiser, 14 Sep. 1868, p. 2. To raise the necessary funds, Thomas exhibited her paintings and sculpture at the J. W. Hine Gallery in Collins Street in March that year. In a letter to the editor of the Argus, art critic James Smith urged the public to support Thomas by the purchase of her works and considered that ‘from the promise she has already exhibited, both as a modeller and a painter, I augur for her a rapid advance under proper instruction’.13 James Smith, ‘Letter to the editor: Miss Thomas’, The Argus, 19 Mar. 1867, p. 5. Sometime around the time of her departure, or soon after her arrival in London in 1867, Thomas began a life-long relationship with Henrietta Pilkington, an amateur artist from Ballarat. The two women spent the remainder of their lives living and travelling together, with Thomas subsequently dedicating her first volume of poetry, Friendship, to Pilkington in 1873.14 Henrietta Pilkington was born in Ireland, c. 1848. She was resident in Australia, exhibiting paintings at the Ballarat Mechanics’ Institute in 1869. Two landscapes of Melbourne surrounds are in the collection of the State Library of Victoria. Pilkington and Thomas were buried together, with Pilkington’s headstone inscribed: ‘The sweetest soul that ever looked with human eyes. Friends for sixty years’. In London, Thomas studied at the South Kensington schools, however, dissatisfied with the tuition, after a year she and Pilkington decamped for Rome in 1868. There she reconnected with Summers, who had established a studio there since leaving Melbourne the year before, and spent time studying and copying works from antiquity.15 A ceramic bust of Pilkington by Summers in a Neoclassical style is dated 1875 and was gifted by Thomas to the collection of Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery. It is now in the collection of the North Hertfordshire Museum. In July 1871, Thomas returned to London and was accepted in the Royal Academy schools, where Summers’s former master Henry Weekes had become Professor of Sculpture. In 1872 Thomas had the distinction of becoming the first female student ever to win the silver medal for modelling. She remained at the Royal Academy schools until 1873 and the following year had her greatest success when six of her portraits (including one of Henrietta Pilkington) were hung ‘on-the-line’ at the Royal Academy annual exhibition. This was a considerable achievement for any emerging artist, and the Australasian reported that, ‘Indeed, we may point with some degree of complacency to the fact that four artists who may be said to have graduated in Melbourne – Miss Thomas, Mr N. Chevalier, Mr Strutt and Mr Charles Summers – have each made their mark in the mother country’.16 ‘The fine arts in Victoria’, Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil, 5 Sep. 1874, p. 91.

Thomas’s brilliant debut at the RA enabled her to make a living through her art. She established a studio in Pimlico, London, where she undertook portrait commissions and taught students privately, and in 1876 was included under the category of ‘professional artist’ in Ellen Clayton’s dictionary English Female Artists.17 Ellen C. Clayton, English Female Artists, Tinsley, London, 1876, pp. 259–60.Thomas can be considered to have had a moderately successful career, having a total of eleven works exhibited at the Royal Academy (1868–77) and exhibiting with the Royal Society of British Artists (1872–81), the Royal Hibernian Academy (1873–95), the Royal Glasgow Institute (1878) and the Society of Women Artists (1874–80). Among her most important commissions were five portrait busts of Somerset-born notables for the vestibule of the Shire Hall at Taunton, including one of author Henry Fielding which brought her considerable publicity, and, in 1892, a portrait bust of Richard Jefferies for Salisbury Cathedral, of which a plaster version was subsequently presented to the National Portrait Gallery in London by the artist in 1897.18 Kedrun Laurie, ‘Margaret Thomas: sculptor of the bust of Richard Jefferies in Salisbury Cathedral’, The Richard Jefferies Society Journal, no. 13, 2004, p. 20. This was to be her last major commission, as from this time Thomas turned her energies to literature, embarking on a new career as a travel writer.

Accompanied by Henrietta, Thomas spent much of the 1890s and 1900s travelling to exotic locations, and writing and illustrating popular ‘travelogues for single lady artists on a budget’.19 ibid. These included A Scamper through Spain and Tangier (1892), Two Years in Palestine and Syria (1899), Denmark Past and Present, (1902) and the illustrations for John Kelman’s From Damascus to Palmyra (1908). She also continued to write poetry. In the 1860s her poems were regularly published in Australian and English newspapers and periodicals, and in the 1880s and 90s they were included in several anthologies of Australian poetry. In 1908 Thomas published her second book of verse, A Painter’s Pastime.20 Another volume of verse, Poems in Memoriam, was published in 1927 after Pilkington’s death. Thomas is also included in Douglas Sladen (ed.), Australian Poets: 1788–1888, Griffith, London, 1888; H. Martin, Coo-ee: Tales of Australian life by Australian Ladies, Griffith, London, 1891; and Lala Fisher (ed.), By Creek and Gully, T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1899. For a discussion of Margaret Thomas’s literary career see Lynn Patricia Brunet, ‘Artistic identity in the published writings of Margaret Thomas (c. 1840–1929)’, Master of Creative Arts (Hons.) thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1993, <http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2316>, accessed 6 June 2018. She also found time to write books on art history and appreciation for the general reader: How to Judge Pictures (1906) and How to Understand Sculpture (1911). Remarkably, the latter carried an addendum in which Thomas commented positively on the recent development of Futurism.21 Margaret Thomas, How to Understand Sculpture, Bell & Sons, London, 1911, p. 165. Thomas finally slowed down in 1911 when she and Pilkington purchased a cottage in Letchworth, Hertfordshire. She died in December 1929 at the age of 87 and was buried in the same grave as Pilkington, who had predeceased her by two years.

Importantly, despite her many years away and like many expatriate artists, Thomas always maintained her connection to Australia. She continued to be identified as an Australian in both Australia and England, was included in anthologies of Australian poetry, and took part in exhibitions of Australian art, including the 1893 Loan Collection of Victorian Art in London. She was certainly not forgotten in Australia at the time and was consistently referred to as an ‘Australian artist’. A review of the 1866 Indian and Colonial Exhibition in London stated that she ‘may be claimed as almost a purely Victorian artist, as she received her art education in this colony’.22 ‘Miss Thomas the sculptor’, Weekly Times, 27 Feb. 1886, p. 4. In 1906 she is described in the first published account of the early history of art in Victoria, William Moore’s Studio Sketches as ‘Victoria’s first woman sculptor’. See William Moore, Studio Sketches: Glimpses of Melbourne Studio Life, William Moore, Melbourne, 1906, p. 68.

In addition to the painted portrait of Summers currently in the State Library of Victoria (SLV), Thomas is known to have painted at least three others and to have sculpted one portrait bust. The earliest known portrait is an oil painting, Portrait of Charles Summers, listed as catalogue no. 122 in the 1866 Intercolonial exhibition in Melbourne (fig. 4, 4a). It has been thought that this was the same work as the portrait now in the SLV, however, the recent discovery by Gerard Hayes, Librarian in the Pictures Collection at the SLV, of a photograph of this work in the 1866 exhibition has confirmed that it is a separate portrait whose current location is unknown.23 Based on this discovery, the SLV has recently redated its portrait to c. 1879 – the time between Summers’s death in October 1878, and the painting’s arrival in Australia in 1880. Joan Kerr in Heritage: The National Women’s Art Book, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1995, p. 37 has erroneously identified the SLV work as the painting exhibited in 1866, as has Michael Galimany in The Cowen Gallery Catalogue, SLV, Melbourne, 2006.

Another painting, also called Portrait of Charles Summers, is in the collection of the North Hertfordshire Museum. It is a small work measuring only 28.7 x 24.0 cm and was exhibited in the Victorian Court of the 1886 Indian and Colonial exhibition in London.24 This was gifted by Thomas to the Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery in 1914. Following the closure of the Letchworth Museum it, together with all of Thomas’s other works in the collection, was transferred to the collection of the North Hertfordshire Museum. This painting closely resembles a photograph of Summers dressed as Michelangelo (fig. 5), thought to have been taken at the Mayor’s fancy dress ball in September 1866 in Melbourne.25 My thanks to Gerard Hayes for informing me that Summers had attended this event as Michelangelo. While the dating of the North Hertfordshire Summers portrait is unclear – and it is certainly small enough to have been easily transported – its close relationship to the photograph indicates that it may also be a posthumous portrait. Very recently, the existence of another painted portrait, most likely dating from before Thomas’s departure from Australia in 1867, has come to light. In 2016 the author was contacted by a member of the public who recalled a portrait of Summers by Thomas which had hung in a family home in Victoria, although its current location is unknown.26 They recalled that the painting was approximately 36 x 28 inches (91 x 71 cm), half-length or less, with Summers wearing an artist’s beret (Summers is not wearing a beret in the 1866 portrait, which indicates they are separate works).

And lastly there is Thomas’s sculpted bust of Summers, which is part of a gallery of ‘Somerset’s most celebrated sons’ commissioned in the late nineteenth century for the vestibule of the new Shire Hall in Taunton, Somerset. Local magistrate R. A. Kinglake was the driving force behind this project, and not long after Summers’s death in October 1878 commissioned Thomas to make a portrait bust of Summers. The bust was installed in mid-1879 and was the beginning of a decade-long relationship, with Kinglake subsequently commissioning another four busts from Thomas for the Shire Hall.27 In May 1879 it was noted in the Australian press that ‘the memorial bust of the late Charles Summers, sculptor, is nearly completed; also that subscriptions to this fund are progressing very favourably’. See ‘Sculpture’, Bendigo Advertiser, 1 May 1879, p. 3.

Accompanying the production of the bust, and presumably as part of the commission, Thomas wrote a short biography of Summers, A Hero of the Workshop and a Somerset Worthy, Charles Summers, Sculptor: the Story of his Struggles and Triumph, which was published in July 1879 and dedicated to Kinglake.28 Despite its brevity and uncritical nature, Thomas’s text can claim to be the first published biography of an Australian artist. The narrative is a simple piece of storytelling that follows the convention of the hero’s journey implied in the title: born into humble circumstances, through a combination of native talent and hard work, Summers overcomes all obstacles to achieve the highest honours. In justifying Thomas’s inclusion into the pantheon of ‘Somerset Worthies’ Thomas repeatedly emphasises Summers’s ‘genius’ and total dedication to ‘art’, writing that, ‘While in culture some have surpassed him [an allusion to his working-class origins and lack of formal education] regarding the gift of genius, he was second to none…’.29 Thomas, A Hero of the Workshop and a Somerset Worthy, Charles Summers, p. 33. During the nineteenth century, the concept of artistic genius; of an individual working through a gift of inspiration and imagination, was valued above all others and allowed the artist to transcend otherwise rigid class barriers. At the same time, to allay any fears of artistic bohemianism, Thomas stressed Summers’s moral virtue: ‘None of the common weaknesses of men can be attributed to him; he neither drank nor smoked, nor devoted himself to the frivolities of dress and fashion’.30 ibid. p. 32. Her concluding statement, that ‘he was as much beloved as a man as he was admired as an artist’, is surely a personal reflection, speaking of her genuine and deep affection for Summers.31 ibid. p. 26.

Summers’s death was also felt in Australia where, despite his absence for more than a decade, he remained very much in the public eye, with many of his works prominently displayed in the Gallery. In January 1879 the dedication of his four sculptures of the royal family was a major occasion for the Gallery and extensively reported in the local press. At their unveiling, trustee Redmond Barry made special mention of the recently deceased artist whom he described as ‘a diligent man of genius whom we may almost claim as a citizen of Victoria, who laboured hard here for many years, and who has made his name ever memorable…’.32 ‘Town news: presentation to the National Gallery’, The Australasian Supplement, 11 Jan. 1879, p. 1. Certainly there were those in Melbourne, presumably including the influential Barry, who considered that Summers should be publicly commemorated, and a suggestion was made that a marble bust should be commissioned for the Gallery.33 ‘Melbourne: from our own correspondent’, Geelong Advertiser, 13 Jan. 1879. There was precedent for this, for example, in 1869 a memorial bust of the actor G. V. Brooke was funded by public subscription for the Gallery (the sculpture was executed by Summers).34 Lurline Stuart, ‘Fund-raising in colonial Melbourne: the Shakespeare statue, the Brooke bust and the Garibaldi sword’, The La Trobe Journal, no. 29, April 1982, <http://www3.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-29/t1-g-t1.html>, accessed 18 Aug. 2016

Did Thomas sense an opportunity here? We do not know if she knew of these discussions back in Melbourne, but around this time she began another portrait of Summers – although whether it was with the NGV as a potential purchaser in mind is not known. This is the painting, Charles Summers, c. 1879, now in the collection of the SLV. It is first recorded in mid-1880 when Thomas submitted it to the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition, where it was reportedly accepted by the hanging committee, although not hung due to lack of space.35 In August 1880 it was reported that the work was ‘accepted … for the last exhibition’, presumably the summer exhibition in 1879. (See ‘Town news’, The Australasian, 28 Aug. 1880, p. 19.) The work indeed bears a Royal Academy Exhibition label from 1880 which gives its title as ‘The late Charles Summers, Esq. Sculptor’. I am grateful to Gerard Hayes for providing this information.

Thomas immediately dispatched the portrait to Melbourne, and it arrived at the end of August in time to be included in the British Court in the International Exhibition, which opened in October 1880. In May of the following year it was reported that the NGV trustees were ‘in treaty’ with Thomas for the purchase of the portrait. While we do not have any further records of these negotiations, in July 1881, Thomas presented it to the Gallery – a possible consolation being the Gallery’s purchase of her medallion of Redmond Barry a few months earlier.36 Margaret Thomas, Sir Redmond Barry, 1856, SLV. This work is entered in the NGV stock books on 9 March 1881 as being purchased from the artist for ‘3.3.0’, and is presumably the work now in the SLV collection (H39356). Thomas also offered casts of her medallion for sale at three guineas. (See ‘Our Melbourne letter’, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 Jan. 1881, p. 7). One of these casts is in the collection of the NGA (79.2243).

The SLV portrait is the largest and most imposing of all of Thomas’s portraits of Summers and speaks directly to an Australian audience. While Summers is depicted wearing a beret and artist smock, it is the inclusion of a statuette of his Burke and Wills monument that suggests Thomas most likely had Melbourne in mind for its eventual home.37 Small plaster versions of Summers’s maquette for the Burke and Wills sculpture are in the collection of the Ballarat Art Gallery and the Royal Society of Victoria (72.5 x 35.5 x 29.0 cm). A larger plaster version is in the collection of the Warrnambool Art Gallery (118 x 70 x 54 cm). For a discussion of their relationship to the monument see Gerard Hayes, ‘Melbourne’s first monument: Charles Summers’ Burke and Wills’, La Trobe Journal, no. 42, Spring 1988, <http://latrobejournal.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-42/t1-g-t2.html>, accessed 6 June 2018. As much as it was a clever ploy to appeal to local audiences, or as a means to identify the sitter as the author of the well-known monument, the inclusion of the statuette creates an additional reading of the painting. For indeed, the painting can be considered to represent not just one but three individuals: Robert O’Hara Burke, William John Wills and Charles Summers. By placing all three men in the same symbolic space, Thomas is able to suggest an equivalence between them: that as much as the explorers Burke and Wills were heroic figures, so too was Charles Summers a ‘hero’ of the early years of art in Victoria. In fact, the three men were close contemporaries – Summers and Burke were born just four years apart – and all emigrated to Victoria within a year of each other during the gold rush. It is even possible that their paths had crossed in Melbourne.

It was widely acknowledged that Summers had played an important part in the artistic development of the colony, not only as an artist but through his active role in the establishment of the first artist societies and close involvement with the Gallery. This was clearly articulated in the Gallery’s letter to Thomas in July 1881 thanking her for presenting to the Gallery, ‘the portrait of an artist so closely identified with the art history of Victoria’.38 Letter from the National Gallery of Victoria to Margaret Thomas, 28 July 1881, SLV archive. I am grateful to Gerard Hayes for bringing this letter to my attention. The portrait was similarly referred to in a contemporaneous newspaper column as being ‘of interest as one of the pioneers of art education in this colony’.39 The Leader, 27 Aug. 1881, p. 21. The portrait was immediately placed on display and was the first portrait of an Australian artist to enter the Gallery’s collection.40 The next portrait of an artist was acquired in 1891: John Longstaff’s 1886 portrait of Frederick Folingsby, the first appointed Director of the National Gallery and Head of the Gallery school.

From its inception, the Gallery had collected both what it termed ‘locally produced’ works (the foundation of the NGVs current ‘Australian art collection’) as well as works from overseas (the ‘International art’ collection). Portraits were actively acquired in both categories, with the Australian works primarily being of notable individuals associated with the history of the colony – a kind of portrait gallery of Victoria’s ‘founding fathers’ (for, unsurprisingly, there were no portraits of women) within the larger gallery.41 The first acquired portrait of an Australian woman appears to have been of the writer and journalist Jessie Couvreur, nee Huybers, known as ‘Tasma’, by Belgian artist Mathilde Philippson. It was gifted to the Gallery in 1897 and is now in the collection of the State Library of Victoria. I would here refer you to the work of Alison Inglis in respect to the establishment of a de facto ‘portrait gallery’ during the early years of the NGV and its role in the construction of colonial cultural identity. By the 1880s, Melbourne was keen to leave behind its raw origins as a brash gold-mining town. It had grown into a leading city of the Empire with cultural aspirations. A report on the opening of the Victorian Academy of the Arts Gallery noted that this was ‘satisfactory evidence that we are not exclusively engrossed by the pursuit of material objects in this gold-producing colony, but that the studies which elevate and the arts which adorn life occupy a fair share of attention, and are cultivated with success’.42 Australian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil, 5 Sep. 1874, p. 91. In the Gallery, Summers’s portrait, alongside those of colonial governors, politicians, clergy, explorers and pastoralists thus also served to represent the progress of culture and the arts within the young colony.

Thomas depicted Summers as an artistic genius and heroic figure in her portraits and published biography of him, yet for the most part these categories did not apply to females in the nineteenth century. However, in a remarkable self-portrait, Thomas quite literally paints herself into a complex picture of artistic production and construction of masculine artistic identity. In her Portrait of an artist, c. 1882 (North Hertfordshire Museum), Thomas shows herself seated in a fashionable aesthetic interior, brush and palette in hand, looking towards a portrait of a male subject on an easel. The painting’s title, Portrait of an artist, can be applied as equally to Thomas as to the male portrait. It is not too much to suppose that the portrait is intended to represent Summers, who had only recently passed away and was the most significant male figure in her life; whose portrait Thomas had painted and sculpted no less than five times since the 1860s. Tellingly, Thomas exhibited Portrait of an artist alongside her Portrait of Charles Summers (North Hertfordshire Museum) in 1886 at the Indian and Colonial Exhibition in London, Thomas thereby making her own agency in the creation of Summers’s portrait crystal clear.

While Summers has always been acknowledged as an important figure in the early cultural development of Victoria, it is Thomas who emerges as a real hero of nineteenth-century art in Australia. There are many distinctions and ‘firstisms’ in her remarkable career: one of the first Australian-trained artists; Victoria’s first female professional sculptor and the only woman known to have been modelling and carving large-scale sculpture in any of the Australian colonies during the 1850s and 1860s;43 Joan Kerr, Heritage: The National Women’s Art Book, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1995, p. 462. the first female artist to be awarded a silver medal in the Royal Academy schools in London; the most successful professional female Australian artist of the late nineteenth century; a multiple exhibitor at the Royal Academy; the author of the first biography of an Australian artist; and author of two books on art, in addition to her published poetry and travel writing.

Thomas is also central to the history of the NGV. In 1881 her portrait of Charles Summers was the first oil painting by an Australian female artist to be acquired by the Gallery and the first to go on display in the NGV. Was it also the first ‘locally produced’ work by a female artist to be acquired by the NGV? It turns out it was not. There were several others – the Gallery’s 1879 catalogue lists a pencil drawing called View of Launceston by a ‘Miss Black’, acquired in 1869, and a watercolour called Tasmanian Flowers by a ‘Miss Blyth’, acquired in 1872. However an even earlier Gallery catalogue of 1869 lists a portrait medallion of the musician Charles Horsley by the very same Margaret Thomas. The Gallery’s stock books record that it was gifted to the Gallery by the artist sometime after 1866, when another cast of the medallion was exhibited in the 1866 Melbourne Intercolonial exhibition. This medallion, like many of the Gallery’s early works, is now lost. However, as it predates the Black drawing and Blyth watercolour, it appears to be the first ‘locally produced’ work by a female artist to enter the collection and is certainly the first sculptural work by a female artist to have been acquired by the Gallery.

Thomas’s portrait of Charles Summers remained on display in the Gallery for many years, until the 1940s when the modernising program of incoming NGV director Daryl Lindsay saw the deaccessioning of much of the NGV’s early collection. The by now deeply unfashionable nineteenth century works were considered to be of little more than historic interest, and were either sold or transferred to other public institutions, with many subsequently lost or destroyed through neglect. Fortunately, Thomas’s painting survived this fate and was transferred, together with many other early portraits, to the NGV’s sister institution, the State Library of Victoria. It remains in the SLV collection, a rare and treasured example of the work of this heroic female artist.

Elena Taylor, Senior Curator of Art, UNSW Sydney

Notes

The question of what the first work by an Australian female artist to be acquired was revolves around the definition of who is considered an Australian artist. This is a problematic concept if narrowly defined by place of birth or citizenship rather than place within Australian art history. The same criteria must be applied to Thomas as to artists like Tom Roberts, who is always considered an Australian artist. Like Thomas, Roberts was born in England and came to Australia as a child, and both received their first artistic education and began their careers in Australia. Ellis Rowan’s 1887 watercolour, Flower painting, purchased in 1890, was incorrectly identified in Jennifer Phipps, Creators & Inventors: Australian Women’s Art in the National Gallery of Victoria, The Gallery, Melbourne, 1993, as the first work by an Australian female artist to enter the collection. Phipps would have been correct to call Rowan the first ‘Australian-born professional’ female artist, however, whether the amateurs ‘Miss Black’ or ‘Miss Blyth’ (whose works were acquired in 1869 and 1872 respectively) were also Australian-born, is not known.

This paper was delivered at the conference ‘Human Kind: Transforming Identity in British and Australian Portraits, 1700–1914’, 8–11 Sep. 2016, University of Melbourne.

The year of Summers’s arrival in Australia has previously been given in various publications as either 1852 or 1853. R. T. Ridley confirms the date as 16 Jan. 1854, when Charles Summers, his wife Augustina, two of his siblings (Albert and Elizabeth) and his father George arrived in Melbourne on The Hope. See footnote 10 in R. T. Ridley, ‘The mysterious James Gilbert: the forgotten sculptor 1854–85’ in La Trobe Journal, no. 54, March 1995, <http://latrobejournal.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-54/latrobe-54-031.html>, accessed 6 June 2018.

Margaret Thomas, A Hero of the Workshop and a Somerset Worthy, Charles Summers, Sculptor: The Story of His Struggles and Triumph, Hamilton, Adams & Co, London, 1879, p. 27.

These are listed in Ken Scarlett, Australian Sculptors, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980, p. 624. All were deaccessioned in the 1940s under the directorship of Daryl Lindsay. In 1996 the NGV purchased two marble busts by Summers.

The monument was, however, not completed until September 1866, when the last of four bas-relief panels were attached to the pedestal.

These sculptures were deaccessioned in 1941 by incoming NGV Director Daryl Lindsay and given as permanent gifts to public entities. They were installed outdoors, which led to their degradation through exposure. See Gerard Vaughan, ‘The cult of the Queen Empress: royal portraiture in colonial Victoria’, Art Journal, NGV, vol. 50, <https://ngv-assets.exhibitionist.digital/essay/the-cult-of-the-queen-empress-royal-portraiture-in-colonial-victoria/>, accessed 6 June 2018.

‘The exhibition of fine arts’, The Argus, 5 Jan. 1863, p. 5.

Letter from the National Gallery of Victoria Trustees to Margaret Thomas, 28 July 1881, Library Trustees’ Outward letter-book 1875–1890, Australian Manuscripts Collection, SLV, pp. 391–2. I am grateful to Gerard Hayes, Librarian in the Pictures Collection at the SLV, for bringing this letter to my attention.

I have not been able to confirm where the often-repeated claim that she was ‘one of the first three students granted permission to draw from the plaster casts in the National Gallery’ first originated. Presumably it came from Thomas herself.

While from 1863 there had been calls for the establishment of an art school associated with the Gallery, the first School of Design was only established in association with the Gallery in June 1867. Although it is possible that Thomas was briefly enrolled just before leaving for England, it is more likely that her access to the casts was facilitated by Summers, in the period before the establishment of the School of Design. See Kathleen M. Fennessy, ‘For “love of art”: the Museum of Art and Picture Gallery at the Melbourne Public Library 1860–70’, The La Trobe Journal, no. 75, Autumn 2005, p. 13, <http://latrobejournal.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-75/t1-g-t2.html>, accessed 6 June 2018.

The exact date of her departure is not known; however the Geelong Advertiser of 14 Sep. 1868 mentions her departure 15 months earlier, making it sometime around July 1867. See ‘Current topics’, Geelong Advertiser, 14 Sep. 1868, p. 2.

James Smith, ‘Letter to the editor: Miss Thomas’, The Argus, 19 Mar. 1867, p. 5.

Henrietta Pilkington was born in Ireland, c. 1848. She was resident in Australia, exhibiting paintings at the Ballarat Mechanics’ Institute in 1869. Two landscapes of Melbourne surrounds are in the collection of the State Library of Victoria. Pilkington and Thomas were buried together, with Pilkington’s headstone inscribed: ‘The sweetest soul that ever looked with human eyes. Friends for sixty years’.

A ceramic bust of Pilkington by Summers in a Neoclassical style is dated 1875 and was gifted by Thomas to the collection of Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery. It is now in the collection of the North Hertfordshire Museum.

‘The fine arts in Victoria’, Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil, 5 Sep. 1874, p. 91.

Ellen C. Clayton, English Female Artists, Tinsley, London, 1876, pp. 259–60.

Kedrun Laurie, ‘Margaret Thomas: sculptor of the bust of Richard Jefferies in Salisbury Cathedral’, The Richard Jefferies Society Journal, no. 13, 2004, p. 20.

ibid.

Another volume of verse, Poems in Memoriam, was published in 1927 after Pilkington’s death. Thomas is also included in Douglas Sladen (ed.), Australian Poets: 1788–1888, Griffith, London, 1888; H. Martin, Coo-ee: Tales of Australian life by Australian Ladies, Griffith, London, 1891; and Lala Fisher (ed.), By Creek and Gully, T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1899. For a discussion of Margaret Thomas’s literary career see Lynn Patricia Brunet, ‘Artistic identity in the published writings of Margaret Thomas (c. 1840–1929)’, Master of Creative Arts (Hons.) thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1993, <http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2316>, accessed 6 June 2018.

Margaret Thomas, How to Understand Sculpture, Bell & Sons, London, 1911, p. 165.

‘Miss Thomas the sculptor’, Weekly Times, 27 Feb. 1886, p. 4. In 1906 she is described in the first published account of the early history of art in Victoria, William Moore’s Studio Sketches as ‘Victoria’s first woman sculptor’. See William Moore, Studio Sketches: Glimpses of Melbourne Studio Life, William Moore, Melbourne, 1906, p. 68.

Based on this discovery, the SLV has recently redated its portrait to c. 1879 – the time between Summers’s death in October 1878, and the painting’s arrival in Australia in 1880. Joan Kerr in Heritage: The National Women’s Art Book, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1995, p. 37 has erroneously identified the SLV work as the painting exhibited in 1866, as has Michael Galimany in The Cowen Gallery Catalogue, SLV, Melbourne, 2006.

This was gifted by Thomas to the Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery in 1914. Following the closure of the Letchworth Museum it, together with all of Thomas’s other works in the collection, was transferred to the collection of the North Hertfordshire Museum.

My thanks to Gerard Hayes for informing me that Summers had attended this event as Michelangelo.

They recalled that the painting was approximately 36 x 28 inches (91 x 71 cm), half-length or less, with Summers wearing an artist’s beret (Summers is not wearing a beret in the 1866 portrait, which indicates they are separate works).

In May 1879 it was noted in the Australian press that ‘the memorial bust of the late Charles Summers, sculptor, is nearly completed; also that subscriptions to this fund are progressing very favourably’. See ‘Sculpture’, Bendigo Advertiser, 1 May 1879, p. 3.

Despite its brevity and uncritical nature, Thomas’s text can claim to be the first published biography of an Australian artist.

Thomas, A Hero of the Workshop and a Somerset Worthy, Charles Summers, p. 33.

ibid. p. 32.

ibid. p. 26.

‘Town news: presentation to the National Gallery’, The Australasian Supplement, 11 Jan. 1879, p. 1.

‘Melbourne: from our own correspondent’, Geelong Advertiser, 13 Jan. 1879.

Lurline Stuart, ‘Fund-raising in colonial Melbourne: the Shakespeare statue, the Brooke bust and the Garibaldi sword’, The La Trobe Journal, no. 29, April 1982, <http://www3.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-29/t1-g-t1.html>, accessed 18 Aug. 2016.

In August 1880 it was reported that the work was ‘accepted … for the last exhibition’, presumably the summer exhibition in 1879. (See ‘Town news’, The Australasian, 28 Aug. 1880, p. 19.) The work indeed bears a Royal Academy Exhibition label from 1880 which gives its title as ‘The late Charles Summers, Esq. Sculptor’. I am grateful to Gerard Hayes for providing this information.

Margaret Thomas, Sir Redmond Barry, 1856, SLV. This work is entered in the NGV stock books on 9 March 1881 as being purchased from the artist for ‘3.3.0’, and is presumably the work now in the SLV collection (H39356). Thomas also offered casts of her medallion for sale at three guineas. (See ‘Our Melbourne letter’, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 Jan. 1881, p. 7). One of these casts is in the collection of the NGA (79.2243).

Small plaster versions of Summers’s maquette for the Burke and Wills sculpture are in the collection of the Ballarat Art Gallery and the Royal Society of Victoria (72.5 x 35.5 x 29.0 cm). A larger plaster version is in the collection of the Warrnambool Art Gallery (118 x 70 x 54 cm). For a discussion of their relationship to the monument see Gerard Hayes, ‘Melbourne’s first monument: Charles Summers’ Burke and Wills’, La Trobe Journal, no. 42, Spring 1988, <http://latrobejournal.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-42/t1-g-t2.html>, accessed 6 June 2018.

Letter from the National Gallery of Victoria to Margaret Thomas, 28 July 1881, SLV archive. I am grateful to Gerard Hayes for bringing this letter to my attention.

The Leader, 27 Aug. 1881, p. 21.

The next portrait of an artist was acquired in 1891: John Longstaff’s 1886 portrait of Frederick Folingsby, the first appointed Director of the National Gallery and Head of the Gallery school.

The first acquired portrait of an Australian woman appears to have been of the writer and journalist Jessie Couvreur, nee Huybers, known as ‘Tasma’, by Belgian artist Mathilde Philippson. It was gifted to the Gallery in 1897 and is now in the collection of the State Library of Victoria. I would here refer you to the work of Alison Inglis in respect to the establishment of a de facto ‘portrait gallery’ during the early years of the NGV and its role in the construction of colonial cultural identity.

Australian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil, 5 Sep. 1874, p. 91.

Joan Kerr, Heritage: The National Women’s Art Book, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1995, p. 462.